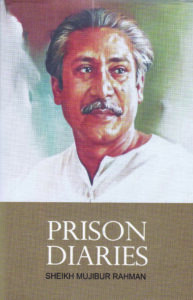

Prison Diaries

Karagarer Rojnamcha: A Jail Diary with a Difference

Ahmed Ahsanuzzaman

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's entire life bears testimony to his lasting love and passion for Bangladesh and Bengalis.His grand metamorphosis from his parents' 'Khoka' to the Father of the Nation is a telling illustration of thekind of man he is, exceptional in the extent of his sacrifice; a truly people's leader; Bangabandhu, the Friend of Bengal!

Mujib's Aushamapta Atmajiboni (Unfinished Memoirs), published in 2012, narrates in a leisurely pace how he became instrumental in Pakistan politics. Reading Karagarer Rojnamcha (“Diary in Jail”) published by Bangla Academy this last March alongside Atmajiboni, one recognizes right away that both are works by the same hand.The effortless, conversational pitch of the narrative will attract readers of both works immediately. Bangabandhu passed almost one-fifth of his life in jail because of autocratic Pakistani rule. His view of jail is that of an insider who knew it as his“home away from home”for years.The dramatic beginning of Rojnamcha immediately sets the tone of the book: life in prison is altogether a different kind of existence from home life: “Those who have not been to the jail, those who have not experienced life in jail, do not know what jail is.”

Rojnamcha has three major sections, the first of which provides a comprehensive account of jail customs and conventions. With amazing wit, Mujib offers us the jail shabdakosh (prison dictionary). In jail, prisoners are known by the dophas, the specific jobs, they perform. Hence the writer dopha, the writer department, which accommodates educated convicts, assigned secretarial jobs involving writing letters and keeping accounts. There is also saitaner kal (Satan's mills). In these mills, blankets are made for prisoners. It is called thus because those who work there are so draped in white, soft fibrous substances that they look devilish! The section ends with a fairly long account of one Ludu Mia whose story reveals the extent to which the villainy of society turn an innocent person like him into a criminal.

The second section collects diary entries written between 2 June, 1966, and 22 June 1967. 1966 of course, was a tumultuous year as far as the history of Bangladesh is concerned. Bengalis were agitating then for the 6-point demands announced by Bangabandhu while the provincial governor Monayem Khan was attempting to foil the movement. The diary entries reveal a tense Bangabandhu immersed in his thoughts about East Bengal and concerned over the wholesale arrests and detention of his compatriots, some of whom were mere boys. He scans the newspapers but is not surprised to find any coverage of the hartal in them. The press published a government note, but it was the same old unbelievable government line about police opening fire to protect them. That the same note mentions ten deaths make Mujib shiver in fear as he reads it because it is easy for him to see that the actual number of deaths would be much higher.

In the diary, Bangabandhu is extremely critical of leaders like Maolana Bhasani, so adept at sudden disappearances because of “political illnesses.” Mujib questions Bhasani's integrity since he had kept mum when government atrocities had reached their peak; then a group of pro-Bhasani “progressive (!)” activists had even given grist to the mill of government propaganda by calling the Awami League movement “secessionist.”

Sheikh Mujib also has a go at Bengali opportunists who are ready to sell their country for petty personal gains. He notes: Bangladesh is so fertile that while "golden crops grow here” so do "weeds and parasitical plants.”And he is aware of the Bengali trait of parasrikatorota, sheer and unmotivated jealousy. He finds in the unity of the crows he sees in and around the prison a striking contrast to human treachery. He even finds their unity inspirational: “Occasionally the crows will come in hundreds to protest in unison. In my heart I appreciated their united resistance”.

The undated pages of Karagarer Rojnamcha, written sometime in 1968, comprise the final section of Rojnamcha. The short editorial note to the section informs readers that Mujib had been arrested at the jail gate in the early hours of 18 January, 1968 on charges of treason framed in connection with his involvement with the so-called Agartala conspiracy, and that he was then confined in the officers' mess in Kurmitola. The narrative in this section is devoid of the humor one finds elsewhere in the book. This was because he had not met his family for months and was being denied access to any reading material or his party mates anymore; earlier, he would ever enjoy seeing them pass him by inside prison every now and then. However, in Kurmitola cantonment he was being made to live absolutely alone. He would come out of solitary confinement only in the evening for walks when he would be escorted by two armed soldiers. Bangabandhu curses his fate at this time because he is unable to speak in Bangla, while living in his beloved East Bengal!

Rojnamcha reveals Mujib's simplicity, amiability and hospitality and concern for others. His attire reveals how quintessentially Bengali he is in his dress as well as his personality: he is seen there in his lungi, jama and genji (263). At times Mujib even plays the chef; on one occasion he is seen cooking what he feels is a hotchpotch dish. His fellow prisoners who get to taste it, however, say, "Not bad at all!” We also see him send and receive flowers on Pohela Baishakh. Even in prison, on 17 March, detained party leaders do not waste the opportunity to celebrate his birth anniversary. The city Awami League even sends him a big cake then. His wife and children join him as well and there is quite a party for him—in jail!

Karagarer Rojnamcha shows us Mujib juxtaposing his public self with his private one in prison.Alone inside the cell he thinks about his ailing parents, wife and children. He does not consent to his elder daughter's marriage proposal—“she is studying, let her study, pass the IA and BA. Then we will see to it”. He inquires about his children's education and younger daughter as a concerned father would. Prison life is hard for him as we see when he records his encounter with his 3 year old younger son, Russell, who had hardly seen his father, and who initially in jail visits would want him to accompany them home. Sadly, Mujib writes on his birthday in 1967, “Russell too has begun to realize what is happening; now he does not want to take me home”. One also notices the deep love Mujib has for his wife, Begum Fazilatunnesa Mujib. He feels completely indebted to her, for it is she who takes care of the family in his absence; in addition, she gives him the support he needs to stand by his people. Mujib also feels he does not have to worry overmuch about his family because she is keeping their home in order.

In her perceptive and insightful introduction, his eldest child Sheikh Hasina retells the amazing story of the twice-found manuscripts. On both occasions—the first soon after the liberation war and the second on 12 June, 1981, when Bangabandhu's house on Road 32, Dhanmandi in Dhaka was handed over to the survivors of the August 15, 1975 massacre—she went to their house and discovered the manuscripts, which also included the exercise books of Atmajiboni. She informs readers that the title Bangabandhu himself selected for Rojnamcha was Thala Bati Kambal/Jelkhanar Sambal (A plate, a bowl and a piece of blanket/are the only things one gets when in prison). She points out that Karagarer Rojnamcha records the splendid, unselfish sacrifices of the Father of the Nation for which we now have an independent Bangladesh where can live with dignity. She pays rich tributes to her mother, a far-sighted woman who had inspired her husband to write when in prison. She had sent the khatas to jails and made sure that the manuscripts were collected as soon as he walked out of them. One can imagine the tears she holds back as she concludes her Preface "Over and again Ma comes to my mind” (16).

Karagarer Rojnamcha is surely a significant addition to the genre of prison literature as well as the history of Bangladesh. Against the background of his life in prison Bangabandhu has unveiled the emergence of a nation with remarkable ease. It is a sort of an epic of a nation and its hero struggling and facing immense odds to give it birth.

Ahmed Ahsanuzzaman is professor of English at Khulna University